Remembering the "smell of death"

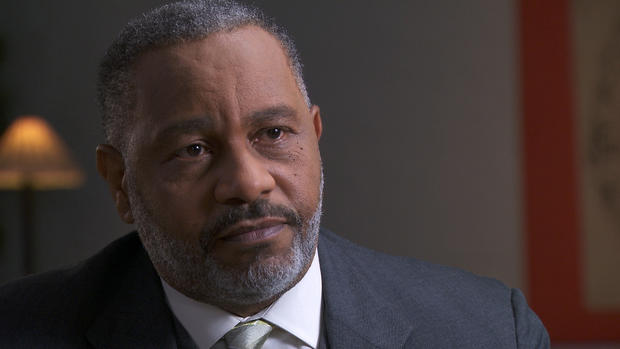

Ray Hinton was 30 years old when he was convicted of killing two restaurant managers and sent to Alabama’s death row. He was 57 when the U.S. Supreme Court overturned his conviction, paving the way for a new trial, which exonerated him. On 60 Minutes this week, Scott Pelley interviews Hinton and two other exonerated prisoners about how it feels to spend years in prison on a false charge -- and what it’s like to finally walk free.

In the previously unaired clip above, Hinton describes death row as “a place of horror,” where the “smell of death” from the electric chair wafted through the air.

“When you smelled that smell did you think, ‘I’m next?’” Pelley asks him.

“Oh, of course,” Hinton says. “Anybody that’s on death row, you have to think about -- it could be you next time.”

While Hinton was on Alabama’s death row, 54 prisoners were executed and several others took their own lives. The electric chair is no longer used as a primary execution method in any state, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Since July 2002, Alabama has used lethal injection instead.

Hinton says it was his abiding faith in God, instilled in him as a boy by his mother, that helped him survive decades in prison, often confined to an 8-by-5 foot cell. “My faith teaches me that God may not come when you want him,” he says, but “he always on time.”

For Ken Ireland, another exonerated prisoner, DNA played a crucial role in proving his innocence, 21 years after he was arrested for the rape and murder of a mother of four in Connecticut. But those years in prison took their toll. After he was finally released, Ireland tells Pelley, he would sometimes barricade himself in a walk-in closet out of fear that someone would kick down his door and drag him back to prison.

Ireland says he also felt out of step with the post-prison world he encountered, particularly when it came to technology. “It’s sort of like waking up from a coma, it really is,” he says in the clip above. “I went in a coma in 1988 when, you know, cars were square and, you know, you had rotary phones.” Now, he says, “you’ve got the entire knowledge of mankind ever in this little cellphone that you carry in your pocket with you.”

Yet, surviving such an unimaginable ordeal put life’s minor annoyances -- like a traffic jam -- into perspective. When he found himself stuck in traffic soon after his release, Ireland says he actually thought, “this is great,” because it was so much better than his life in prison. “I mean, there’s not a whole lot you can do to me now that’s going to really rattle me,” he says.

As the 60 Minutes story explains, Ireland was relatively fortunate, if you can call it that, because he received compensation from the state of Connecticut for his wrongful imprisonment. Many states offer no compensation, and almost none help exonerated prisoners get back on their feet. That rankles attorney Bryan Stevenson, who worked on Hinton’s case for 16 years and founded the Equal Justice Initiative, a law firm founded in part to overturn false convictions. He says we owe exonerated people financial support, health care -- and more.

“We owe them an investigation into what went wrong,” he says. “I think by failing to take seriously the needs of innocent people who are exonerated, we kind of say we don’t care if we get it wrong. We don’t care if we execute innocent people. And I think that’s a terrible thing for a society that claims to be about justice and fairness to assert.”

Editor’s Note: These videos were originally published on January 10, 2016. Since then, Ken Ireland left his job at the Connecticut Board of Pardons and Paroles, bought an RV and is traveling across the United States, making up for lost time.