The journey to autism diagnosis: Earlier is better, families say

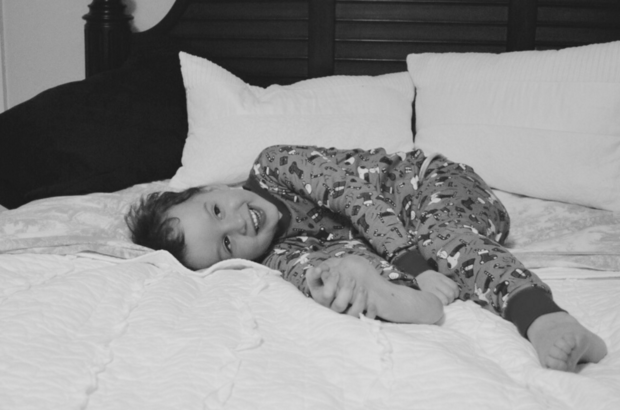

Finn was an easy baby, said his mom, Meg Murphy.

He'd play on a blanket with one little toy for hours. "We just thought he was really laid back," Murphy, a mother of three from Downingtown, Pennsylvania, told CBS News.

Her antennae started going up when she and her husband Billy noticed changes with Finn's language. He had started using normal baby words such as "mama," "dada" and "babba," but then he stopped.

"They faded out over time. He would start flapping his hands when he was excited. He wouldn't look when you called his name," she said. They thought he might have hearing problems because he'd had ear infections.

After trouble-shooting with an ear, nose, and throat specialist, tests came back normal on Finn's hearing. He was also checked for seizure issues and cleared. Meg's mom, who had worked in schools over the years, suggested that there may be developmental issues, but Murphy said she brushed the concerns aside, and was actually a little irritated at the suggestion.

"I remember at that time that our pediatrician wasn't concerned. He was like, all kids mature at different rates. But our family members, and my mom in particular, said this wasn't normal," said Murphy.

Finally, to be thorough, they asked their pediatrician for a referral to early intervention services -- state services that can help evaluate or provide special education or therapies and other support to families with children who have disabilities or delays.

"They come to your house -- a child development specialist and a speech therapist -- and they just tried to play with him. He was 14 months old. We thought we were just checking off a box. But at that visit, he didn't want to have anything to do with any of it. He couldn't play with the toys the right way. He didn't want to be with new people," she said.

Finn scored very low on all of the assessments.

"I remember being really devastated," Murphy recalled, but she said it was also a dawning: she realized she needed to harness resources to help her son.

Speech, occupational and physical therapy began for Finn, for an hour every week.

"They worked with him individually and also taught me how to engage Finn and how to work with him. Before, I'd leave him to play nearby me on his own while doing dishes or other things but because of early intervention, I realized that I really had to get down in his face. He hated it. I remember trying to get him to do puzzles, putting big plastic coins in a plastic bank, playing with shape sorters. I have two other kids now, too, and they just love to pick up toys and do it on their own. We had to teach Finn to do it hand over hand, and give him lots of breaks," she explained.

A formal diagnosis came when Finn was about 17 months old, through doctors at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, where the family now visits every six months to check in with autism experts.

When Murphy was newly pregnant with her second child, and Finn wasn't yet two, genetic tests came back showing Finn had two markers for autism.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Finn's condition, is a neurodevelopmental disorder whose causes are still unclear. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 1 in every 68 children in the U.S. has autism. A government survey out late last year suggests the condition may be even more common than that. More boys than girls are diagnosed with autism, the hallmarks of which include ongoing social and communication impairments, and repetitive behaviors or activities. The word "spectrum" refers to the fact that there not a single snapshot of what's normal for autism, but a range of severity and behaviors in children.

"Forty years ago, our definition of autism was different. It was less inclusive. It wasn't that autism didn't exist, it was just viewed differently," Leandra Berry, a pediatric neuropsychologist and associate director of clinical services for the Autism Center at Texas Children's Hospital, told CBS News.

Berry said she's diagnosed children as young as 14 months. Sometimes, though, a diagnosis doesn't come until years or even decades later. "Really there's no upper age limit. People are getting diagnosed even as adults," she said.

"The younger a child is diagnosed the better, said Dr. Patricia Manning-Courtney, director of The Kelly O'Leary Center for ASD, and a professor of pediatrics in the Division of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center.

However, there is controversy over whether all young children should be screened for autism, or only those whose parents or doctors raise concerns about their development.

Screening for all?

In a statement published in the Journal of the American Medical Association this week, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force said there's insufficient evidence to show that universal screening for autism spectrum disorder in all kids ages 18 to 30 months old is justified.

The task force is an independent panel made up of volunteer experts that makes recommendations about certain preventive care services including screenings, counseling services, and medications. The group's statement pointed out that no study has directly compared the long-term outcomes of children who received screening with those who didn't, and that research showing the effectiveness of early autism treatment has not been based on cases identified through screening.

A commentary in JAMA Pediatrics by Duke autism expert Geraldine Dawson noted that the president of the American Academy of Pediatrics said the task force's recommendations "run counter" to the academy's 2006 recommendation to screen all children for autism at ages 18 and 24 months. Dawson said that screening leads to earlier referral and diagnosis.

"The current guidelines that encourage universal autism screening offer the best chance for individuals with ASD to reach their full potential and lead productive lives. We should, therefore, stay the course while continuing to advance our knowledge about the full impact of autism screening," she wrote.

An editorial in JAMA Psychiatry criticized the task force as well for its "non-recommendation."

"We hope that the USPSTF statement does not trigger a step backward to later diagnosis, later treatment, and more disparity in services for children with ASD," wrote Dr. Jeremy Veenstra-VanderWeele of the Sackler Institute for Developmental Psychobiology, Department of Psychiatry, at Columbia University, and Dr. Kelly McGuire of with the Center for Autism and Developmental Disorders, Maine Behavioral Healthcare, in Portland.

Berry told CBS News that autism screening at a typical "well child" checkup does not carry any risks, and does not involve any special procedures -- there's no MRI or blood tests, for example. It requires a brief parent questionnaire that takes five or ten minutes to complete, which is good at identifying children who need further assessment for autism or other developmental conditions that may have similar early symptoms, she said.

Manning-Courtney said, "I've never seen a family resent or regret going through this process. I've seen families appreciate being attentive to these issues. And often these families are relieved."

What's important is that parents make a connection very early with a child who might have autism or other developmental issues, she said. If the screening raises red flags, children would next visit with a specialist like herself.

"We give a combination medical exam, and psychological and speech language evaluation," she explained.

If a child is diagnosed, Manning-Courtney said they can benefit from starting the needed therapies sooner.

"They get resources sooner. Families get everything they can get sooner. At a professional level, its much easier, too, if I know a child from a young age on versus picking them up from age five or seven," she said. "It's better to start the conversation sooner and get children into therapy sooner rather than later."

Finn's mom said she's glad she followed her instincts and pursued answers early, as hard as it was initially to face the knowledge that he had autism. The information led to early interventions for Finn, which she believes benefitted him and their whole family.

On Finn's third birthday, he started full-day preschool where he received autism support classes. Another big step, after weighing the pros and cons with their education and medical experts, was adding medication to his plan. He recently started a very low dose of Risperdal, for anxiety and irritability, said Murphy.

It was a difficult decision, she said, but the right one. "It's been huge for him. Aside from getting his own full-time aide in school, starting the medicine was the best thing for him. It helps him visibly. He's more comfortable in his own skin. It took down a wall. It helps him sleep at night, which was huge for us. He would be up at all hours of the night and that would affect his day. And it doesn't make him sleepy during the day," said Murphy.

Her second son, now two-and-a-half, received a complete evaluation for autism at 13 months, and he did not have any signs of the condition. Her six-month-old daughter hasn't been evaluated for autism yet, but is developing well, Murphy said.

"I know so many other moms who are scared to know. Or they say, 'He'll catch up or grow out of it.' For us, it was so important that we put our parental pride aside and made sure that we were giving Finn the best opportunity for help early on," she said.

Cost and access

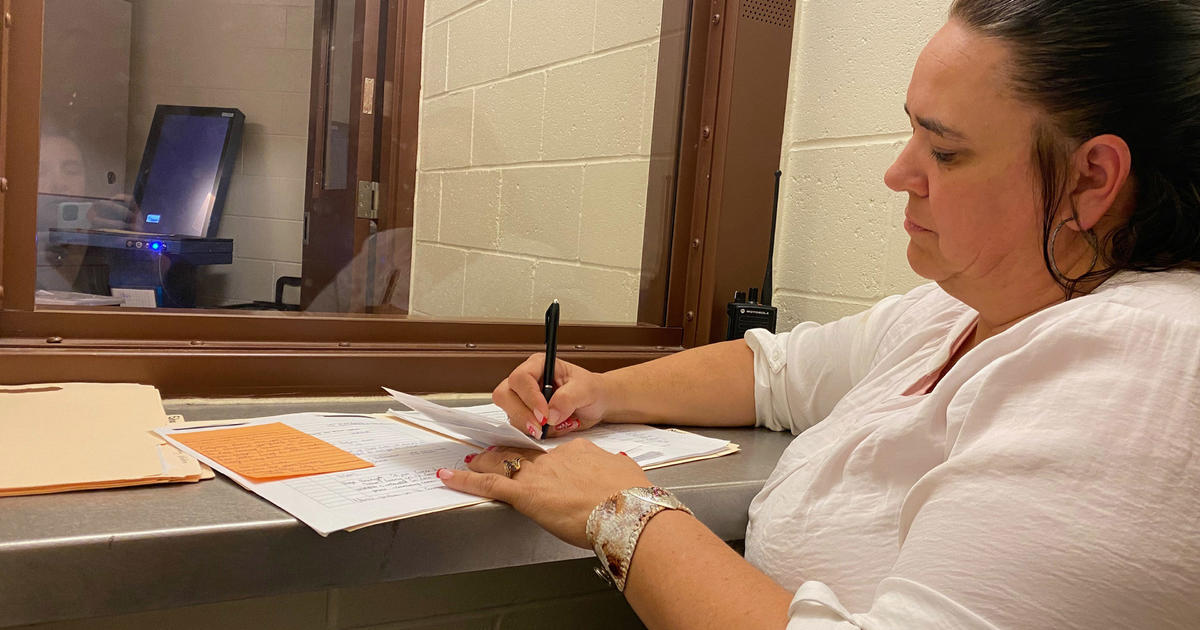

For many families, the cost of such treatments can be a difficult burden. Sheletta Brundidge, a Houston mom of four who has two toddlers with autism, said speech and behavioral services add up.

But you can't cut out therapies your child needs, she explained. "If your child has autism, therapy once a week for 30 minutes is not enough," she said.

Brundidge told CBS News autism can bankrupt even educated, well-off middle class families. But many parents don't realize that there are grants available to families who don't have access to free or affordable autism support services in their communities or health insurance that covers all of their child's needs, she said.

To help other families, Brundidge volunteers her time, providing local seminars for parents who want to learn about autism funding opportunities.

Murphy's son Finn, now almost five, is considered severely autistic. He doesn't talk and is not potty trained. But he now communicates in his own way, his mom said. He uses YouTube videos -- Sesame Street and Disney sing-a-longs -- that he shows her to tell her if he's hot or hungry, for example.

"He has them memorized and can play certain bits of other peoples' conversations to communicate," Murphy said.

Murphy said she's learned a lot by reading blogs by older autistic children who don't speak but can type, which allows them to "talk" online.

"This handful of kids learned how to type and can express everything now. Through them, they have been a window. A lot of these older kids whose blogs I read ask why are researchers not researching that?" Murphy said.

She holds hope that Finn will one day be able to express himself through typing, too.

Finn has also participated in ski boarding camp for kids with autism, horseback riding, and youth soccer, where he gets his own teenage buddy.

"He's gotten a lot better. What I'd say to other parents is not to be scared of the limitations that a diagnosis can imply. But instead to learn to see your child as a really different individual who is just as intelligent and special as every other kid, but just displays and learns and communicate differently," Murphy said.

Murphy feels that all children should be screened for autism at 18 and 24 months.

"While our Finn displays more 'classically autistic' traits that would make it less likely for him to slip through the diagnostic cracks, there are many kids on the spectrum who don't display obvious autistic behavior, or are better at 'passing' as typical. Girls especially. This group of kids could really greatly benefit from early diagnosis. For obvious reasons like access to educational supports and therapies, but also for less obvious and equally important reasons -- like building self esteem and self awareness skills. What a gift it would be to help these kids find their tribe early on."