Breaking through autism with Disney movies

Parents of autistic children dream of breaking through the barrier that keeps them apart, which is why one family's accidental discovery of a "way in" to the child they thought they'd lost seemed like nothing short of a miracle. Our Cover Story is reported by Lesley Stahl of "60 Minutes":

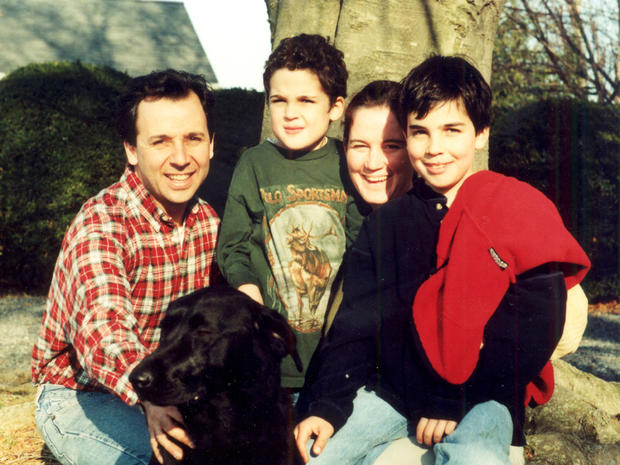

Ron and Cornelia Suskind will never forget the fear and confusion they felt when, within a period of three weeks, their chatty, energetic, nearly three-year-old son, Owen, vanished.

"And very engaged," said Cornelia.

And then . . . nothing.

"It was like trying to find clues to a kidnapping -- where did he go?" said Ron.

"He was developing completely normally -- what happened?" asked Stahl.

"I think the first thing that we noticed was that he stopped sleeping," said Cornelia. "And then he started to lose eye contact. And then he started to lose language" -- down to one word: juice.

It was 1994. Ron, then a reporter for the Wall Street Journal, and Cornelia, a stay-at-home mom, were frantic.

"It was the most devastating, horrifying thing to go through," said Cornelia, "because of course I thought I had done something wrong."

Ron added, "We're quizzing each other - Did you see something? Did you see something? We thought maybe he banged his head when we weren't looking."

Doctors had a different diagnosis: autism.

All the Suskinds knew of autism was the movie "Rain Man": "We said, 'That can't be our son,'" Ron said.

That was in the '90s. Today parents are all too aware that one in 68 children in the U.S. is diagnosed with this developmental disorder.

For Ron and Cornelia, their new normal was a little boy unable to communicate, disinterested in the world around him. The only thing that seemed to make him happy was watching Disney movies, for hours on end.

"He just sits and watches them," Ron said, "and it seems to give him a kind of comfort."

It was those Disney movies that would change Owen's life.

After nearly four years without speaking, Owen suddenly had something important to say. The occasion was his older brother Walter's birthday.

"Walter gets emotional kind of one day a year, on his birthday," said Ron. "And on his 9th birthday, he gets a little emotional. And Owen looks at us quite intently like something's coming, and he says, 'Walter doesn't want to grow up, like Mowgli or Peter Pan.'

"It's a very evolved thought," Ron laughed, "and it's full speech. Cornelia said it's like a lightning bolt went through the kitchen."

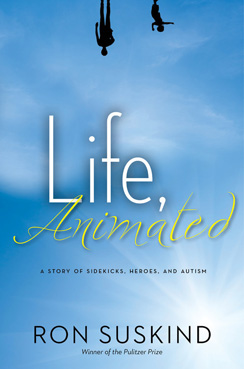

As Ron recalls in a new book, "Life, Animated," something in Owen's mind had unlocked -- and those Disney movies seemed to be the key.

Suskind continued: "So up I go into Owen's bedroom, I grab a puppet, which is one of his favorite characters, which is Iago. I crawl over to the bed, so he doesn't see me, I put the bedspread over my head and I push the puppet up through the crease in the bedspread, and I talk to him as Iago. I say, 'Okay, Owen. What does it feel like to be you?' And Owen turns to the puppet like he's bumping into an old friend, and he says, 'It's not good, and I have no friends and I'm lonely.'"

Suskind stayed in character: "We talked, Iago and Owen, for about two minutes. And of course, it's our first conversation for four years."

Stahl asked him, "Do you remember when your dad started to talk to you as if he was one of the characters?"

"Yeah," Owen said. He described it as "amazing."

And what did he learn from the Disney movies? "When I grew up watching them, I learned how they could help me find my place in the world," he said. "That they could help me with the ways of life, and how you should live."

And that's not all: At eight years old, Owen taught himself to read by sounding out the films' credits, down to the grips and the best boys.

And the movies inspired him to draw his favorite characters -- not the heroes, but the "sidekicks" -- the characters he could relate to.

"Owen, at that point, saw the world for what it is," said Suskind. "He saw other kids racing forward when he's caught on the starting blocks. And he said, 'I am not the hero. I am the sidekick. I help others fulfill their destiny.'"

Kevin Pelphrey, who directs the Child Neuroscience Lab at Yale, said, "Individuals with autism have rich experiences, rich feelings, rich emotions -- those can be harnessed to help them learn, to engage with the world."

Pelphrey says that autistic children's obsessions -- which parents are often told to try and limit -- can instead be used in therapy. "This is sort of a new approach in thinking about taking that one thing and really making it central to the child's social world," he said.

Pelphrey is conducting a study that uses brain imaging to measure the effects of these treatments -- which he calls "affinity therapy" -- on autistic children. "And so you can know early if a treatment is working, and critically you can know if it's not," he said. "And you can alter it. You're not wasting time. The dream is to make it work better for each individualized child based on what you can get from their brain data."

With Kristin Holland's seven-year-old son Parker, his therapists are now trying to use his love of farm animals as a "way in."

"For Parker we saw a huge improvement," said Holland. "through the therapy we saw him sort of get interested in other people."

For families like the Hollands and the Suskinds, finding any door into the world of their autistic child is a miracle.

For Owen, Disney is also a way out, as he sang "That's What Makes the World Go 'Round," from "The Sword in the Stone."

Don't just wait and trust to fate,

And say, that's how it's meant to be.

It's up to you how far you go

If you don't try, you'll never know.

And so my lad, as I've explained,

Nothing ventured, nothing gained.

"Wow, is that Merlin singing?" said Stahl. "So what did you get out of that? What did you learn from Merlin singing?"

"To try new things, exciting things. of my place in the world," said Owen.

Owen's world -- once just his TV and Disney tapes -- now even includes a serious girlfriend, Emily.

Stahl asked Owen, "Now what movie helped you there?"

"I gotta say 'Beauty and the Beast,'" said Owen, quoting the dialogue:

BEAST: "I've never felt this way about anyone. I want to do something for her. But what?"

COGSWORTH: "Well, there's the usual things -- flowers, chocolates, promises you don't intend to keep ..."

LUMIERE: "Ahh, no no. It has to be something very special. Something that sparks her interest."

Three years ago, with Emily's help, Owen started a Disney Club on campus for classmates who love Disney as much as he does. He told Stahl he did it "to find people a lot like me."

And he did.

For the first time in his life, at Disney Club, Owen is more than a sidekick. He's a leader.

He introduced the film: "Tonight we watch some of 'Beauty and the Beast.'"

Stahl asked a question to those in the Disney Club: "Which Disney character speaks to you most?"

One boy said Simba, from "The Lion King": "Because he's strong and he's not as scared as he was as a kid."

Another said the Beast: "Because when he's an animal he kind of has incredible strength."

Owen's answer: "Aladdin, because he wants to show people that he's more than just a nobody. Show them that he's a happy diamond in the rough. And he is. Just like me!"

"So am I," said another.

The students sang along with the film -- and Cornelia Suskind cried.

"Yeah, it was really overwhelming to me," she told Stahl. "You know, they have a rich inner life that is every bit, if not richer, than yours and mine. And many of them have great difficulty expressing that to the rest of the world, to their families. But it doesn't mean it's not in there."

For more info:

- ronsuskind.com

- "Life, Animated: A Story of Sidekicks, Heroes, and Autism" by Ron Suskind (Kingswell); Also available in eBook format

- Read an excerpt from "Life, Animated" by Ron Suskind

- Follow Ron Suskind on Twitter and Facebook

- lifeanimated.net

- What is autism? (From autismspeaks.org)

- Yale Child Neuroscience Lab, Yale University

- Riverview School, Cape Cod, Mass.

- Disney Club hits a high note (Cape Cod Online)